by Tim Warren, Policy Lead for Palliative and End of Life Care, Scottish Government

My mum lives eight hours away, within earshot of Glastonbury (if only her hearing was a little better). Her frailty is a pressing reality. All of the issues which press in at work – frail older people, most with a host of health issues, increasingly lacking capacity, exhausted family carers, stretched paid carers, the role of GPs, district nurses; it all feels very personal.

My mum lives eight hours away, within earshot of Glastonbury (if only her hearing was a little better). Her frailty is a pressing reality. All of the issues which press in at work – frail older people, most with a host of health issues, increasingly lacking capacity, exhausted family carers, stretched paid carers, the role of GPs, district nurses; it all feels very personal.

As the policy lead for palliative and end of life care at the Scottish Government, I frequently have to answer questions about what I do. I usually begin with how ignorant I was when I took on this role, when I mistakenly thought palliative care was basically about hospices and cancer. Of course, I now appreciate that the lion’s share of palliative care is about supporting frail older people like my mum.

When does care become palliative?

So, good care, provided to people at any stage of their care pathway, becomes palliative with hindsight when the person dies. Specialist palliative care, provided in any setting is clearly ‘palliative’. From this perspective, good care, provided in care homes, or by informal carers, supported by district nurses and GPs, and encompassing the spiritual, social and psycho-emotional and the physical, is also ‘palliative care’.

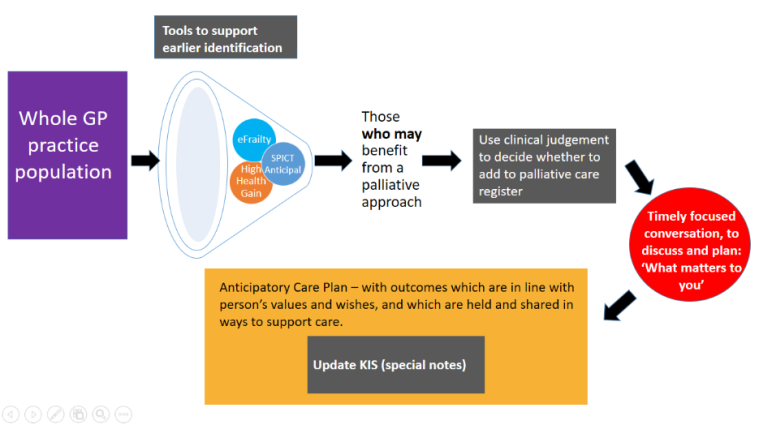

The strategic framework for action on palliative and end of life care (SFA) starts with support for identifying people who stand to benefit from a holistic palliative approach, highlights the importance of conversations with those people (and those who care about and for them), and then aims to provide coordinated care across all settings.

So, who might benefit from a palliative approach?

At what point does support for people with long term conditions become early palliative care? I have come to think about this in two ways. Firstly, thanks to Kirsty Boyd, consultant in palliative care at Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, I possess the mental metaphor of “umbrella conversations” – conversations to be carried on, not just when it’s raining, but when it might rain. Such conversations might be initiated with a question like, “If you were to get more unwell, what would it be important for us to know about”. Not having these sorts of conversations early, and recording them in a sharable way, can rob people of care and dignity at the end of life. And, although the National Digital Service will in due course enable such information sharing, at the moment the only available mechanism for reliable sharing across settings is the Key Information Summary.

Secondly, another way of looking at who might benefit is by employing “20:20 hindsight”, and reviewing the profiles and care pathways of those who have died over the most recent available year. In 2017 almost 58,000 people died. Around 16,000 of those died suddenly. Of the remainder around 20,000 died with dementia. This gives an additional significance to having those conversations early.

Why early conversations matter

As a policy team we get to see the letters people send to ministers about the care their loved ones receive. One haunts me. It recounts the last months of the writer’s father’s life, in which he experienced increasing frailty, repeated hospital admissions and disjointed care (along with some examples of kind, warm and compassionate staff). He underwent several operations, repeated burst stoma-bags, unmanaged pain and broken promises of ‘fast-tracked care’. The family said it had seemed like a dreadful rollercoaster, which could have been prevented had they just had a realistic conversation about his likely trajectory, and what mattered to him.

Although not all care pathways are like those of this man, all of those who died expectedly should have benefited from conversations about what mattered to them. Paul Baughan, a GP and the Healthcare Improvement Scotland clinical lead for palliative care, led the development of a new palliative care Directed Enhanced Service, to provide some financial support for identifying those who may be moving towards death. (We worked together on the diagram below). It aims to increase the proportion of those with a KIS at the end of life, but especially people with frailty, who have more often been overlooked.

And it is brilliant to see a focus on ensuring that people in care homes get to benefit from this approach; the work in Edinburgh and Glasgow comes to mind. There is lots still to do, but the support of colleagues in primary care in doing this, and supporting them to do so feels like a key element in making sure that everyone gets the palliative care they need by 2021.